Chinese Imperial Era Furniture

INTRODUCTION

Depending on its function, an Imperial era piece of Chinese furniture typically belonged to one of three different categories: bedroom furniture, study room (library) furniture, and hall furniture, where a hall itself might belong one of a number of categories such as a state (official government) hall, a temple hall, a garden hall and a residence hall, the latter of which was further subdivided into a royal residence hall and a residence hall for a high-ranking government official, an artist, or a wealthy businessman. The ancient Chinese term for a hall, covering all of the above applications, was “ting”.

In the following, a short description of specifically Imperial era Chinese hall furniture will be presented, followed by a presentation of the general features that characterize first Ming (CE 1368-1644) Dynasty furniture, then Qing (CE 1644-1911) Dynasty furniture – both viewed from a general style & materials perspective, i.e., irrespective of the bedroom-study-hall distinctions outlined above.

HALL FURNITURE

In time, the hall became more widespread, such that even lesser government officials and general members of the literati as well as sucessful artists had large enough residences to justify the inclusion of a hall. The Chinese name to describe this type of hall was usually “tang”, or chamber. However, both the “ting” (hall) and the “tang” (chamber) served as the room in which to receive guests, and was used almost exclusively for this purpose, much in the same way that a “living room” (American) or a “drawing room” (British) is used to receive guests; on almost all other occasions, the family would dine in the kitchen.

Of course, there was a world of difference between the “living room”/ “drawing room” of an artist or a government official, even a high-ranking government official, and the “living room”/ “drawing room” of an emperor, though the difference was more one of degree than of kind, i.e., the same furniture pieces – one is truly tempted to say “set pieces” in this instance – based on function, were seen in the hall of both the emperor and his subjects, albeit, the set pieces of the emperor naturally outshone the set pieces of his subjects by a large margin (it would probably have been dangerous for a subject’s health were the reverse ever to have been rumored to apply!).

Just as with the “living room” and “drawing room” of America and Britain, respectively (and a similar reception room is common to every European country), the hall, or chamber, of Imperial era China was the room in the house with the most exquisite – and most expensive – furniture. Since the garden was central to the residence of a royal Chinese personage or to a distinguished member of Chinese society, the residence hall was constructed so as to present a view on, and an entrance way to, the garden.

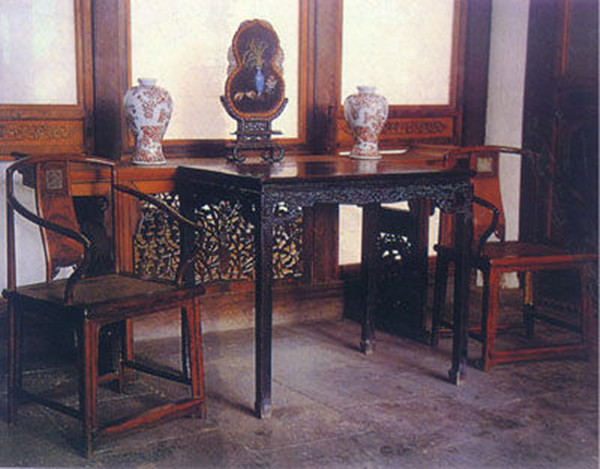

Generally speaking, what one today would call the interior design of an Imperial era Chinese hall followed certain laid-down principles. In the center stood 4 tea tables, each with a set of 2 chairs (8 chairs in all), the walls, on two sides, featured specially carved wainscoting, while the walls on the other two sides were plain, though on each was hung a decorative panel.

In addition, ranged alongside the walls in a certain specific order were serving tables, clothes racks, folding screens (i.e., room dividers) and traditional Chinese-style beds, known as arhat beds. Most hall furniture of Imperial era China was made of mahogany, though Chinese pear wood and its later substitutes, red sandalwood (zitan) – a form of rosewood – and blackwood (hongmu – sometimes referred to as wu mu), were used to some extent. Chinese red sandalwood, initially in abundance, eventually became a very rare wood by the middle of the Qing Dynasty, therefore Ming or Qing Dynasty furniture made of these two wood types fetch a very high price at international auctions.

References to Ming Dynasty furniture and other furnishings such as vases – invariably signifying things of rare beauty that carry an extremely high price tag – were common in early British and American cinema, and they occasionally occur still, at least on television, such as in the 1986-94 British TV series, Lovejoy, about a somewhat unscrupulous but lovable art dealer who was not only good at producing counterfeit art items himself, but was unparalleled at distinguishing between the genuine and the counterfeit work of others.

To give an idea of the extent to which Imperial era Chinese hall furniture from the Ming and Qing Dynasties is valued today, the following examples:

In Hongkong, a Ming Dynasty mahogany folding screen (folding screens are highly prized, exquisitely crafted, and – where made of mahogany – fetch the highest prices) was in the recent past auctioned off at the price of 1.2 million Hongkong dollars ($155,000 USD, circa), while another mahogany folding screen from the Ming Dynasty period – auctioned off outside China at about the same time – fetched a whopping price of slightly over 2 million Chinese Yuan ($290,000 USD, circa).

More recently, in the city of Shanghai, an auction house sold a group of Imperial era Chinese hall furniture pieces for 300,000 Chinese Yuan, or about $45,000 USD, a near-complete set of Qing Dynasty hall furniture consisting of the standard 4 tea tables and 8 chairs, plus a single armchair.

The Defining Features of Ming and Qing Dynasty Furniture

Ming Dynasty Furniture

Ming Dynasty furniture is usually simple, if somewhat rustic, in design, projecting an image of sturdiness combined with simple elegance, while the furniture of the Qing Dynasty period is more complex and more varied in design, with intricate and luxurious embellishments, projecting an image of delicacy combined with sophistication.

The Ming Dynasty is considered, in hindsight, the golden era in the development of ancient Chinese furniture. This is partly due to the abundance, as yet, of the hard woods used to make furniture during the period, hard woods such as Chinese pear wood (the pear tree, genus Pyrus, which has been cultivated in China since the Western Zhou (BCE 1027-771) Dynasty, originated in China in the foothills of the Tianshan Mountains of Central Asia, from whence it spread north, south and westward, and today grows on every continent) and its later substitute, sandalwood; the increasing demand for furniture had, toward the end of the Ming Dynasty, seriously depleted the stocks of the Chinese pear tree, which was of course also prized for its fruit.

But the later recognition of the Ming Dynasty as the golden era of Chinese furniture was also partly due to two other features of the furniture of this period, namely, the development, on the one hand, of mortise and tenon joinery (think of the way that two pieces of a jigsaw puzzle fit together) – which required no nails, screws or other metal joining devices – and, on the other hand, the dovetailing of design to the intended practical use of the article of furniture in question; in other words, Ming Dynasty period furniture was not fancifully designed for the sake of design itself, meaning that design was not divorced from function. In this same spirit, Ming Dynasty period furniture was neither lacquered, delicately designed, nor embellished with ornate carvings, but was deliberately designed to be simple and sedate, where the natural color and grain of the wood was allowed to speak for itself, as it were. Typical articles of furniture made of Chinese pear wood were large-surface items such as tables, chairs and commodes.

With the depletion of the stocks of pear wood, Chinese furniture craftsmen turned inceasing toward sandalwood and blackwood, as indicated. Unfortunately, the largest sandalwood trees were no more than 25 cm (9.84 in) in diameter, therefore the furniture items made of sandalwood tended to be smaller. The decline of pear wood in the production of furniture continued into the Qing Dynasty, with a gradual shift toward the aforementioned alternative hardwoods. In the meantime, the quality of sandalwood varied both with the variety (there were a dozen or so of these, with red sandalwood being the best) and with the individual specimen, the latter of which also applied to pear wood. This put the ingeniuity of the Chinese furniture craftsman to the test, but he responded creatively to the challenge, reserving the best quality wood – appearance-wise – for the most visible surfaces, while making use of lesser-attractive pieces of wood for the rest.

The main difference between Ming and Qing Dynasty period sandalwood furniture continued to be along the style lines set forth above, where Ming Dynasty furniture was more simple and functional in design, while Qing Dynasty furniture tended toward more elaborate design – perhaps sometimes, design for design’s sake – and ornate embellishments. The most exquisitely crafted – and most expensive – red sandalwood furniture made in China is the so-called Jinxing sandalwood furniture.

Qing Dynasty Furniture

Any analysis of the features that characterize the art of furniture making during the Qing Dynasty would be remisss if it did not view the artistic trends of the Qing Dynasty period in light of what had occurred in this sphere during the previous dynasty, the Ming Dynasty.

For example, in spite of the Qing Dynasty’s problems with foreign governments in general – and with foreign trade within regions of China in particular (it was during the Qing Dynasty period that the humiliating trade and territorial concessions were forced upon China in connection with what China termed the “Unequal Treaties”) – the Western influence on the Chinese furniture artisan that had begun during the Ming Dynasty only increased during the Qing Dynasty.

There were of course other trends and realities that influenced the art of Chinese furniture making during the Qing Dynasty that were wholly divorced from “precedence”, such as the fact that Qing Dynasty rulers were of Manchu/ Jürchen ethnic origin, whereas Ming Dynasty rulers were of Han Chinese origin, and such as the fact that many of the most prized wood types that had made Ming Dynasty furniture famous the world over were either depleted or near depletion by the middle of the Qing Dynasty, meaning that they were in severe decline from the outset of the Qing Dynasty, and this of course had a profound influence on furniture making in China.

The most over-arching features that define Qing Dynasty furniture are outlined below.

INNOVATION

We can be certain that Chinese furniture craftsmen continued to perfect their skills, irrespective of the ruling dynasty, sometimes introducing innovative styles, some of which, during the Qing Dynasty especially, were quite bizarre, such as a bed that attempted to pass for a complete boudoir, as it included clothes racks, hat racks, bottle racks, lamp stands – even a spittoon – and other “accoutrements” whose original purpose cannot be divined today, all of which extra features could be adjusted for height, swung in or out, etc. (this bed puts to shame the modern American reclining chair, with its swing trays for holding glasses, cups, a TV dinner, etc.).

A couple of other Qing Dynasty Chinese furniture oddities, credited to the Chinese author, Li Yu (1610-80), was a “warming chair”, i.e., a chair with a tray under the seat in which hot embers could be placed, and a “cooling bed”, i.e., a bed with a water-tight device under the thin mattress into which cool water could be poured, ensuring a cool, restful sleep even on the hottest summer night.

Another tendency that influenced the art of furniture making during the Qing Dynasty was the fact that the middle class was growing in size, with an ever-greater distribution of wealth, and this not only increased the demand for furniture, but created a demand for new furniture types hitherto unseen, and more embellished furniture, as the bourgeois class began to assert itself. There are many furniture items from this period whose purpose, or function, remains a mystery today, though that doesn’t detract from their value, as antique furniture is of course not purchased for its utilitarian value.

SCARCITY OF RAW MATERIALS

As indicated in the above, the supply of mahogany ran out during the middle of the Qing Dynasty, but it had been in serious decline ever since the end of the previous dynasty. The main Qing Dynasty subsitute for precious mahogany was red sandalwood, which, though slightly less hard than mahogany, was considered by most to be even more beautiful, due to its bright red hue and its distinctive grain patterns in the form of stripes. Red sandalwood was a rare wood, however, so its price guaranteed that it was used only for the most exclusive types of furniture destined for sale to the most exclusive customers. Pear wood was also on the decline, leaving the various other sandalwoods and blackwood as the remaining hardwoods.

These realities influenced the type of furniture that could be made, since many of the trees were small in diameter. Yet, where large specimens were available, Qing Dynasty furniture artisans would go to extremes, sometimes “sculpting” an article of furniture from a single block of wood. Other examples of exorbitance in the art of furniture making during the Qing Dynasty period included fussiness regarding the choice of the individual piece of wood – if it had the slightest blemish, it was rejected. There was also an unwritten taboo against mixing wood types – a given furniture item was made solely of a single type of wood.

This naturally created a great deal of waste of perfectly good furniture-making raw materials, and at a time when the stocks of good furniture-making raw materials were rapidly being depleted, which only drove prices higher, but there was no lack of clientele willing to buy the most exquisite furniture produced by Qing Dynasty furniture artisans (in hindsight, this ‘only the best is good enough’ fussiness regarding raw materials is one of the chief factors that made Qing Dynasty furniture such a lasting, prized work of art the world over, to this very day).

EMBELLISHMENTS

The Qing Dynasty furniture artisan turned his imagination loose, where both delicate design (Ming Dynasty design was simple and stout by comparison) and the use of color, inlays and engravings were given free rein. Decoration, which had been looked down upon during the Ming Dynasty, was deliberately pursued during the Qing Dynasty. In general – in almost every category from design to embellishment – Qing Dynasty furniture eventually went in bold new directions. Since much of the wood available at this time was of slight diameter, Qing Dynasty articles of furniture tended to be smaller, while the range for what constituted furniture seemed limitless, with some articles bordering on what one today might deprecatingly refer to as bric-à-brac.

A COMBINATION OF CHINESE AND WESTERN INFLUENCES

As indicated above, even though the Qing Dynasty eventually placed a ban on the export of Chinese-made furniture, the Chinese furniture artisan continued to allow himself to be influenced by Western traditions, for once the artistic genie is out of the bottle, as it were, it resists being re-bottled. Western-made articles of furniture had made their appearance in China with the arrival of foreign diplomats and foreign merchants, and well-to-do Chinese merchants as well as high-ranking Chinese government officials and members of China’s literati developed a taste for Chinese-made furniture that incorporated elements of both Chinese and Western furniture art.

In a sense, this new, Western current in the the art of Chinese furniture making was part and parcel of the furniture artisan’s unending quest for renewal, and as such was qualitatively no different than the challenges that the transition from Ming to Qing Dynasty styles had presented, which transition was decidedly not abrupt, but gradual, and where much of the Ming style was preserved in early Qing Dynasty furniture. Once begun, however, this Western influence was also encouraged by the Chinese consumer of the era, who considered furniture with a Western influence “in”.

Yet, as regards the incorporation of Western furniture-making techniques and features into Qing Dynasty Chinese furniture making, the Chinese furniture of the Qing Dynasty period remained solidly within the realm of Chinese aesthetics, even though it increasingly incorporated certain Western elements, especially as regards adornment.

Imperial era Chinese furniture made of red sandalwood fetches a staggering price today. As an example of the high price that Qing Dynasty period red sandalwood furniture commands today, an 18th century red sandalwood Chinese table was auctioned off in 1994 by Sotheby’s for the princely sum of $35 million USD, or 239 million Chinese Yuan.